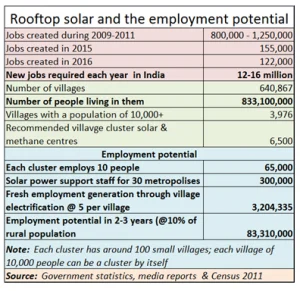

Just look at the table alongside. Some of it deals with the numbers that critics have been bandying around.

Where are the jobs?

During 2015 and 2016, India created just 277,000 jobs. This was lower than the number of jobs created in 2009 to 2011. Yet, there is no denying that one of the key functions of any government is to create jobs, spur demand, and start a virtuous cycle of industrial and economic growth.

However, the job of any government is to overcome odds and create jobs. And there is no better model to study at such times than the one Germany adopted.

Germany shows the way

When the late Hermann Scheer (Energy Minister of Germany in 2000) decided to push for solar power in his country, he had two strategies.

First, he was convinced (he was an electrical engineer who had studied his numbers carefully) that if solar were to be given just 1 percent of the subsidy that the oil industry had enjoyed, he could make the whole world look to solar as the source of energy. He was also buoyed by the knowledge that in the Sahara desert, just 6 hours of sunlight produces enough energy to light up the whole world for a full year.

There was a second strategy in place — to create a middle layer of solar entrepreneurs. This is the part that India’s energy planners have overlooked.

Scheer decided that this layer would comprise small industrialists who would employ people to set up the solar panels on houses (with state funding), maintain them (clean them regularly, for better absorption of sunlight, and also attend to any problems). The entrepreneur would also collect solar power from rooftop solar-paneled houses at a pre-determined price (which came to be known as the feed-in-tariff or FIT and which got adopted by the world over subsequently). The entrepreneur thus aggregated the minuscule solar power outputs from each solar rooftop household, cleaned it up, and supplied a steady stream to the national power grid.

Within a decade, Scheer’s dream was to come true. Bolstered by the German model, and the consequent demand, China stepped in with its large-scale production. Other countries stepped in with innovation. Together, they saw the price of solar power drop from almost 20 cents a unit to less than 3 cents. The dropping prices of solar panels and the sharp drop in battery storage prices has made solar power a mighty competitor to the conventional power grid (notwithstanding what the economic survey tries to say.

But this model led to an unexpected consequence. It is a lesson that India must appreciate. In less than a decade, the solar power industry in Germany began employing more people than even the automobile sector. The middle layer of entrepreneurs was creating employment opportunities that had not been envisaged before. You had the installers, the maintenance people, and small innovators of pieces of electronics that could actually make solar power generation that are much more effective. For instance, someone came up with a brilliant reflector that could convert the weak sunlight of Germany into more focused sunlight.

A lesson for India

Now comes the lesson for India. Remember, Germany has less sunlight, and fewer people, than India. So, obviously, India, with more people (hence, more houses) and much more sunlight, should be having more rooftop solar units. If the solar power exercise was successful in Germany, it should be doubly more successful in India. This country could make the middle layer that much more profitable and vibrant. It could be an excellent solution to India’s need to create jobs.

Of course, the Prime Minister will have to keep at bay the lobbies which support the conventional power grid. There are the power generator s which would try to scuttle the advance of solar power. Then, there are the power grids – owned and managed by state governments – which want to use them to justify losses (usually theft, disguised as losses). And there are the powerful agriculturists – which consume power for industrial purposes clandestinely, yet get the government to show it as agricultural consumption. There is a whole ecosystem which breeds on corruption, inefficiency and political largesse that needs to be dismantled.

How to do it?

The first step is to create village clusters. One effective way is to use 100 villages or so as one cluster. Villages that have population densities of more than 10,000, should be treated as independent clusters (the Census 2011 puts the number of such villages at 3,976).

Each of these clusters is given away to entrepreneurs who back this up with requisite bank guarantees, and agreements that compel them to follow a certain process. The process that has to be followed was covered in these columns a couple of weeks ago.

To make decentralised cluster solar power generation acceptable, rural households may be promised 200 units of free power each month. Any additional consumption would invite payment of market prices. To ensure that the villagers do not arbitrage between stolen grid power and paid-for solar power, it is also essential that all connections to the grid are completely cut off.

What about standby power when the sun isn’t shining? That is where standby batteries with storage capacities of 24-48 hours should be installed with each household, but against a bank guarantee (financed by the state government). The amortization of the battery cost is borne by the cluster entrepreneur. If, for any reason, there is need for additional power, the entrepreneur may resort to the use of a genset. At no time must the connection be allowed to the grid. With batteries that guarantee standby power for 48-72 hours, there is no need to have the grid as a standby. The grid now does not need to subsidise agriculture. The fact that battery prices have already fallen by 70 percent over the past eight years, and the expectation that they should fall by another 70 percent over the next few years, make batteries a cheaper option than grid connectivity.

By dispensing with long grid-based supply lines to villages, transmission losses (and theft) also get curtailed. That will allow grids to give power to industry at Rs 5-6 per unit because there will be little need for cross-subsidy. The lower tariffs for industry and commerce (compared to tariffs of Rs 8-14 at present) will make industry immensely competitive. That should make the wheels of commerce move faster. Prime Minister Narendra Modi will have created the right mood for employment and growth, without subsidies.

Where is the money?

How will the scheme get financed? Simple. The private entrepreneur gets his money from the banks for financing this cluster rooftop solar module. The bank gets it refinanced by an arm of the government which merely capitalises the energy subsidies and losses related to each village cluster. The capitalised subsidies and losses then get bundled as an asset to be backed by bonds floated and guaranteed by the government. This bond issuing company will then play the same refinancing role for the rural power sector that Nabard does for agriculture.

Since the entrepreneur has to make money from families that use more than 200 units, he also plays the role of a catalyst to promote small business enterprises in the cluster. If the commercial venture is successful, the farmer makes money, but so does the entrepreneur. As a businessman, he employs a small army of people to help with the installation and maintenance of the solar rooftop units and the batteries. He employs bright young people who then encourage farmers to use more electricity. For instance, a well-off farmer could be encouraged to install refrigerators and air-conditioners in his house. A poor farmer could be persuaded to buy a lathe machine, or a semi automatic rudimentary harvestor.

The entrepreneur also keeps a sharp lookout for families which try to beat the system by creating more households within the same family (this is what has happened with slums in India.

The results could be electrifying (no pun intended). Each cluster could create jobs for at least 10 people. That alone should create over 65,000 jobs within 8 months (maybe even six). Business development in villages could see incremental employment within the first year itself. That could mean 3.2 million rural jobs. Then work on cities with dense populations, where both roofs and walls could be enabled with solar panels. The potential is mind-boggling.

Within 2-3 years, one can expect at least 10 percent of the rural population to get jobs or start small businesses, or augment their earnings. That should translate into a staggering 83 million jobs.

What is equally important is that the more one uses solar, the less does one need to import oil and coal. Kerala’s experimentation with solar boats is a great example to bear in mind. Operational costs drop to less than 10 percent, and there is little smog created over the backwaters. Expect similar things to happen to tractors and mechanized harvesters as well.

Add to this methane digestors – but more on that later. That could prevent smoke-filled fireplaces based on firewood. It could help reduce deforestation, and improve the atmosphere.

The reduced coal and oil consumption for electric generators will mean reduced import of oil and coal as well. The scheme would also handily contribute to Modi’s target of power for all.

If executed well, the prime minister could have an unbelievable story to tell – not just to Indians but to the entire world